Faith-based programs that share health care costs growing in NC

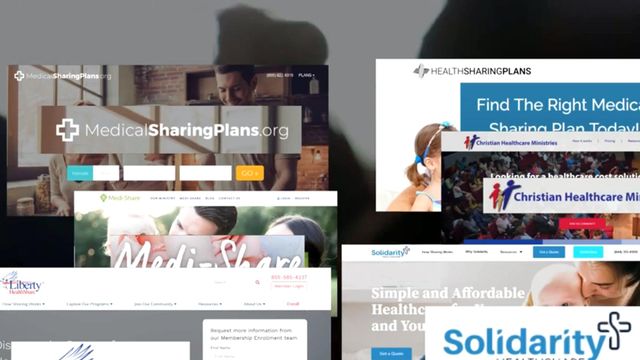

Despite the Affordable Care Act, more than 1 million adults in North Carolina lack health insurance, with many adults and families priced out of insurance plans. In the past year, a growing number those uninsured have turned to health-sharing ministries to help with medical bills.

Posted — UpdatedIn the past year, a growing number those uninsured have turned to health-sharing ministries to help with medical bills.

Caroline and Mark Collie have been health share members for more than a decade through Samaritan Ministries. Instead of paying what most people call premiums, their monthly payments are called shares. One month each year, the Collies send money on behalf of them and their four children directly to Samaritan Ministries. In the other 11 months, they send money directly to other members who have medical needs.

"We have had an amazing experience with them through a number of pregnancies," Mark Collie said. "Every cent of our need we've received in shares from the health care sharing community."

Families don’t have deductibles. They pay out of pocket for any medical bills that are less than what they pay into the system on a monthly basis. If the medical bill is higher, they submit a need to Samaritan Ministries, which decides whether to share that need with other members. If approved, the faith community picks up the tab.

The organization caps most needs at $250,000, though that can go up if families take part in a higher-level program.

The cap came into play for the Collies last September, when a trip to a public pool in Washington, N.C., led to a ruptured blood vessel and bleeding on the brain for 8-year-old Blake Collie.

"It very quickly escalated from, 'I have a headache,' to him holding his head with hands and saying, 'I'm going to die,'" Caroline Collie said.

Blake ended up at Vidant Medical Center in Greenville, where he spent 48 days in intensive care and rehab.

"When you're son is lying in a hospital bed with more things going into him and coming out of him than you can count or describe, the last thing you're thinking about is finances," Mark Collie said.

Once Blake made a positive turn, his father started talking with the hospital about the expenses, which would likely triple what Samaritan Ministries would pay. He also contacted the ministry.

"From that initial call, they were amazing," he said.

Samaritan Ministries agreed to set up a need for the Collies, but that was put on hold after the hospital realized Blake qualified for Medicaid. The family chose that route, and Medicaid covered all of the medical bills.

Mark Collie said he and his wife were prepared to negotiate their bill and get on a payment plan for whatever Samaritan members didn’t cover.

"It would have been a burden on our family, but a burden we looked at and were happy to bear given we have a beautiful 8-year-old boy running around," he said.

While the Collies laud the advantages of health-sharing ministries, they're also aware of the risk in case of a catastrophic event. But that's not true for all consumers across the country, some of whom say they were led to believe the program acted more like insurance.

Regulators in several states are now investigating health-sharing groups, but Samaritan Ministries is not among them.

North Carolina Insurance Commissioner Mike Causey said his office has received about a dozen complaints about health-sharing plans and receives plenty of calls from consumers.

"I'm not opposed to health care-sharing ministries," Causey said. "I believe in the free market, so it is an option, but you don't want people to be fooled into thinking they are insured."

He makes it clear health shares are not insurance: "They have no actuaries. There’s no guarantee that any claims will be paid."

"These are probably not going to pay for preventative care, physical exams," he added. "They may not pay for any prescription drugs, and a medical claim is only what that group deems is a medical claim."

Groups also have different rules when it comes to pre-existing conditions.

With health-sharing coming under the microscope in other parts of the country, Causey said it’s time for them to be regulated in North Carolina. That would require action by the legislature.

"I do believe that, in cases where people have been taken advantage of, that should be addressed," Mark Collie said, adding that knee-jerk regulation would do more harm than good to people like him.

"It would take away [or] further complicate a mechanism for getting health care coverage to a populous that's very much in need of health care coverage," he said.

Collie said he also feels health sharing offers something health insurance, for the most part, doesn’t.

"You tell me which insurance company is going to send you $300 worth of gas cards and a blanket and a handwritten note saying, 'We're praying for your son,'" he said. "There probably are some smaller agencies out there, but I think that would be stretch."

That’s part of the reason the Collies remain with Samaritan Ministries, despite facing a massive medical bill before Medicaid provided a safety net. Once Blake’s immediate health needs are met, the family plans to return to the program.

Related Topics

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.