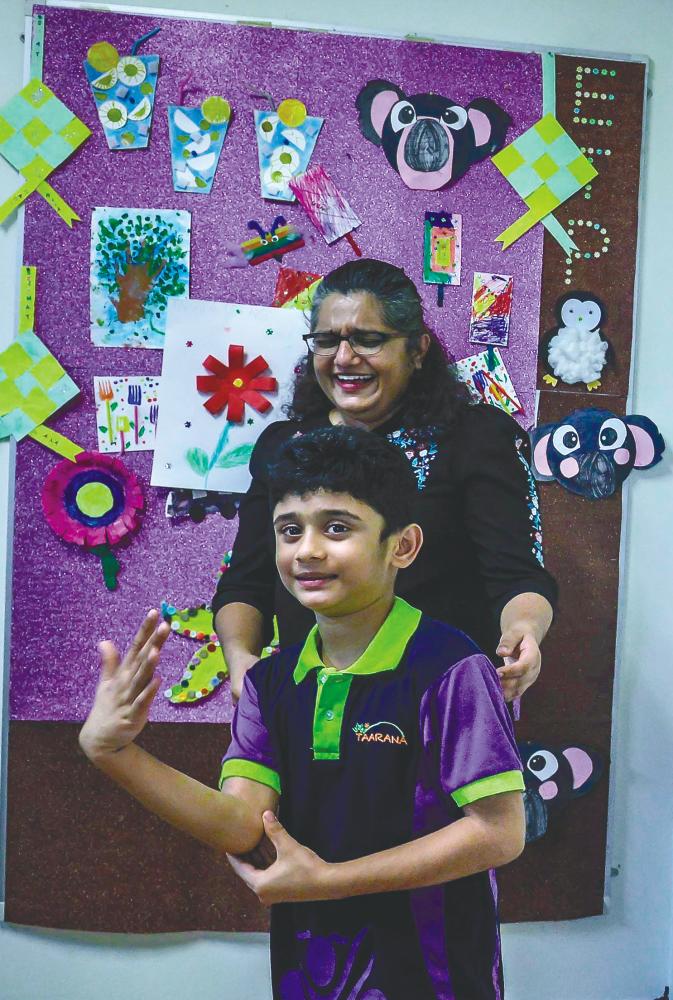

PETALING JAYA: It was several years ago when Assoc Prof Dr Annapurny Venkiteswaran realised something was amiss about her son, Siddarth.

At age two, he had difficulty expressing his feelings in words. Instead, he would grunt to indicate the items or food he wanted.

“He wouldn’t respond to me immediately when I called him. I took him to see a specialist but it was too early. The test conducted was inconclusive.

“I then placed him in a normal nursery. I wanted to see his reaction there, which told me a lot. (The teachers) called me to get him help,” she said at Taarana School, a special needs institution for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), among others.

Siddarth was later diagnosed with autism at another institution, and referred to a psychologist, speech therapist and occupational therapist who helped him with his day-to-day tasks.

But conveying his feelings and thoughts was still challenging.

“At home, he would make different grunts, and our helper would know what it’s for. He’d also point, or take my hand and place it on food, which means he wants it to be prepared for him,” she said.

Through her research and conversations with others with special needs children, she and her son have faced the challenges head-on and now seven years later, Siddarth is beginning to reach his goals in life, including having a go at playing the piano and making new friends.

Annapurny said there are still some minor challenges, especially when Siddarth is out in public, such as biting his nails, breaking a glass at an eatery or suddenly shouting. But the family has accepted that it is part of his growing personality.

Stressed out during the pandemic lockdown recently, Siddarth had broken one of the family’s dining chairs and the television.

“Understandably, he was getting frustrated at not being able to go out, since he’s an outdoors person and we’d often hike every Sunday.

“(His tantrums) were because he couldn’t verbalise (his frustrations) or visit his grandmother. It was a difficult time for us. At one point, we felt lost,” she said.

When the movement control order was lifted, she obtained a letter for Siddarth to study at his teacher’s house.

He spends three hours a day at Taarana, a centre for students with special needs established by RYTHM Foundation in 2011 when the Foundation identified a dire need for resources and support for children and their families. Taarana’s curriculum includes speech therapy, at a cost of RM1,700 per month. Such facilities in the Klang Valley is estimated to cost more than RM3,000 a month, apart from the cost of other coping procedures.

Annapurny said Siddarth has been placed in a government school but in a large group of 12 students and two teachers in a class, it can be overwhelming for him.

It was at the insistence of the teachers that she searched for a private facility that could aid a child’s growth in a one-on-one arrangement.

The number of ASD diagnoses in Malaysia has risen steadily over the past decade, according to Health Ministry data.

The latest figures for 2021 showed that a total of 589 children aged 18 and below were diagnosed with ASD, up 5% from 562 in 2020.

According to a study by the ministry in 2005, which used the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers screener for ASD, its prevalence in Malaysia is between one and two per 1,000 among children aged 18 months to three years. The study also found that boys were four times more likely to have ASD than girls.