Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Doctors are prescribing food to patients with conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

- Programs like "Food Is Medicine" aim to improve health through nutrition education.

- Veterans receive food prescriptions, with $100 monthly for produce, improving health outcomes.

SALT LAKE CITY — Alma Rivera, 35, is expecting her first child next month. But during the pregnancy she developed gestational diabetes, so her doctor decided she and her baby would benefit from specialized nutrition counseling and access to food that's good specifically to counter diabetes. The doctor sent her with a prescription to the University of Utah Health Food Pharmacy.

Oswald "Oz" Hutton, 60, of Salt Lake City, has battled hypertension, arthritis and chronic pain. What you eat makes a difference there, too, so the U.S. Marine Corps veteran opted into nutritional education and access to high quality produce courtesy of a program that's a partnership between the Rockefeller Foundation and the Veterans Health Administration.

Those two programs — and scores of others — are part of the "Food Is Medicine" movement, the belief that what people eat helps determine their health on many levels.

"If you think about the drivers of health, dietary risk factors are shown to be the most important modifiable risk factor for chronic disease and death. Yet in health care, we don't really talk about that much," said Dr. Amy Locke, whose many titles include chief wellness officer at University of Utah Health, professor and co-director of the Driving Out Diabetes Initiative at the Osher Center for Integrative Health.

Locke said modifiable health risk factors are about 20% clinical, 30% behaviors like getting enough sleep or eating well, roughly 10% physical environment and 40% socioeconomic.

"If you have good health care and you have good socioeconomic status, it's easier to eat a healthy diet," she told Deseret News. "What we want to do is use the health care space to leverage those other buckets as much as possible, so we are doing a bunch of 'Food Is Medicine'-related things."

The federal government, health care providers, nonprofits, academics and others are embracing the concept that you can be healthier or sicker depending on what you eat.

The 2022 White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health firmly tied together food and health in its call to end hunger and reduce chronic disease by 2030, as the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion reports. The office said 60% of U.S. adults have some diet-related chronic disease that the right food — and avoiding the wrong ones — can impact. At the same time, there are 18 million people whose households experience food insecurity. The result is an estimated $4 trillion in health care spending.

Deseret News looked at two of the dozens of examples of "Food Is Medicine" programs. How programs operate and who they target varies. But many of them — including the University of Utah Food Pharmacy and the pilot project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation involving Salt Lake area veterans who receive services at the VA — share certain traits: The beneficiaries like Hutton and Rivera have medical conditions that food impacts. Participants are considered food insecure and meet income qualifications.

The programs also both have strong education components to help those benefiting understand why food matters, how to make good food choices and even how easy it is to make good meals.

They also both provide actual food.

Helping veterans get healthy

The Veterans Health Administration hosted a bipartisan Congressional event last week to tout its partnership with the foundation, which just made a $100 million commitment to Food Is Medicine programs, building on its prescription pilot projects in Utah and Texas.

Projects are being launched in Maryland and New York, with partners including the VA, Instacart, Syracuse University, University of Utah, 4P Foods, as well as in North Carolina, Duke University and Reinvestment Partners. The programs have different designs to meet needs in the areas they serve. But the classes, resources and prescriptions are tailored specifically to patients and their chronic conditions.

Hutton is one of 275 veterans in the Utah pilot; the programs combined hope to help 2,000 veterans, while gathering research and looking for ways to tackle diet-related diseases like diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure among U.S. veterans.

Along with food education, veterans in the program are given gift cards worth $100 a month that can be used to buy fruits and vegetables at participating stores. The program lasts 12 months.

Retired four-star U.S. Navy Admiral James Stavridis, foundation board chair, said access to healthy food improves mental and physical health while lowering the cost of health care.

The National Institutes of Health has reported that three-quarters of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan were overweight or obese when they first went to a VA clinic.

Noah Cohen-Cline, director of the Rockefeller Foundation initiative, said the program uses Food Is Medicine initiatives like produce prescriptions, meals tailored to medical needs and groceries that can be prescribed by a clinician as part of medical treatment, "with the big-picture goal of seeing these interventions formally integrated into health care as a covered medical benefit." These pilot projects are testing programs and measuring outcomes.

The foundation would love to expand it to all eligible veterans, including 116,000 in Utah, but Cohen-Cline said philanthropies alone can't meet the need; that requires funding from other sources, including health care systems and insurance companies.

He said it saves money and improves quality of life, making it a great investment.

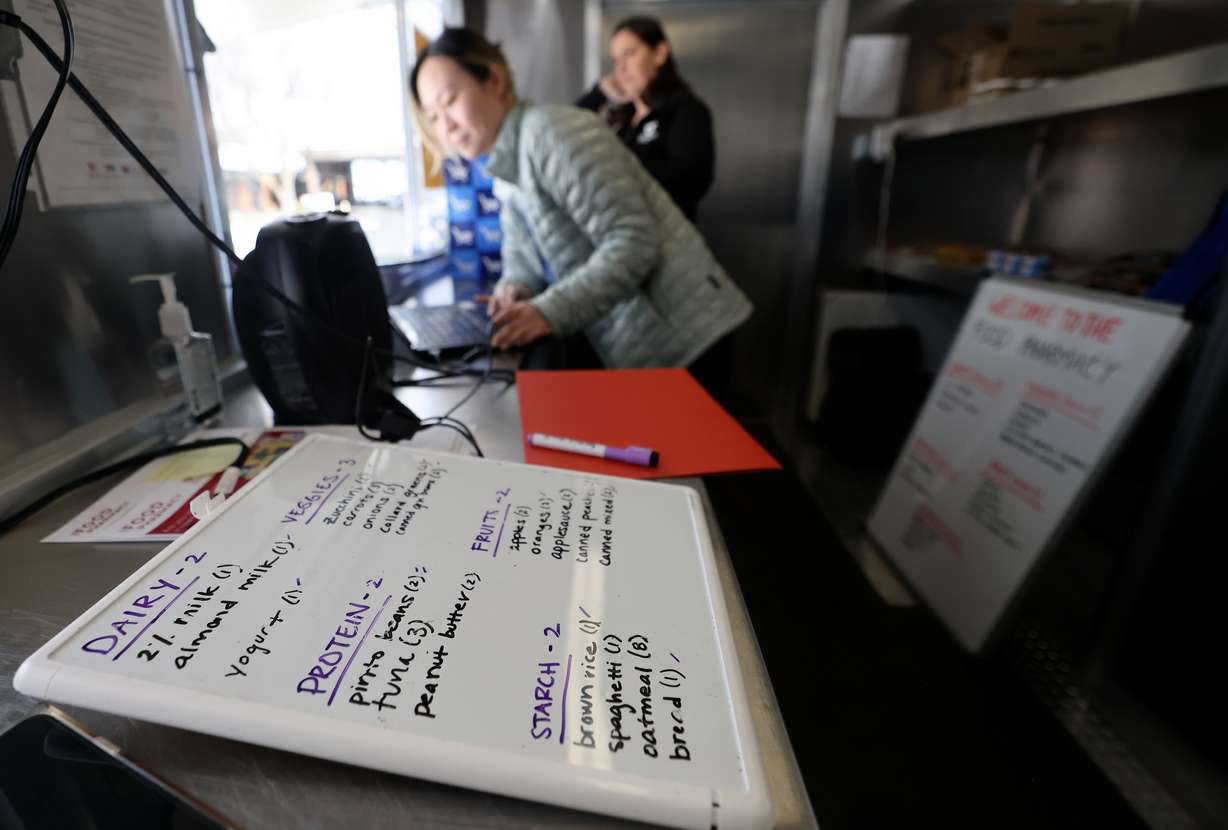

What is a food pharmacy?

The University of Utah Health System, through its integrative medicine department, teaches students in health-related fields how to talk about food as a wellness tool and also how to eat a healthy diet themselves.

"Food is the most significant modifiable risk factor. You should not show up at a medical facility and not have the opportunity to talk about food," Locke said.