Ya Gana Mohammed was asleep in her bed, her husband dozing at her side and her seven children breathing softly in the warm October night, when the militia came. The Boko Haram fighters rampaged through her small town, which hugs the shore of Lake Chad in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno state, shooting civilians, snatching children, looting and wreaking havoc. She bolted from her home as panic gripped the town. “As I ran away, you could hear them executing people,” she says. Her husband was among those killed. Then, in the melee, “four of my seven children were taken by the militia. I don’t know what happened to them.”

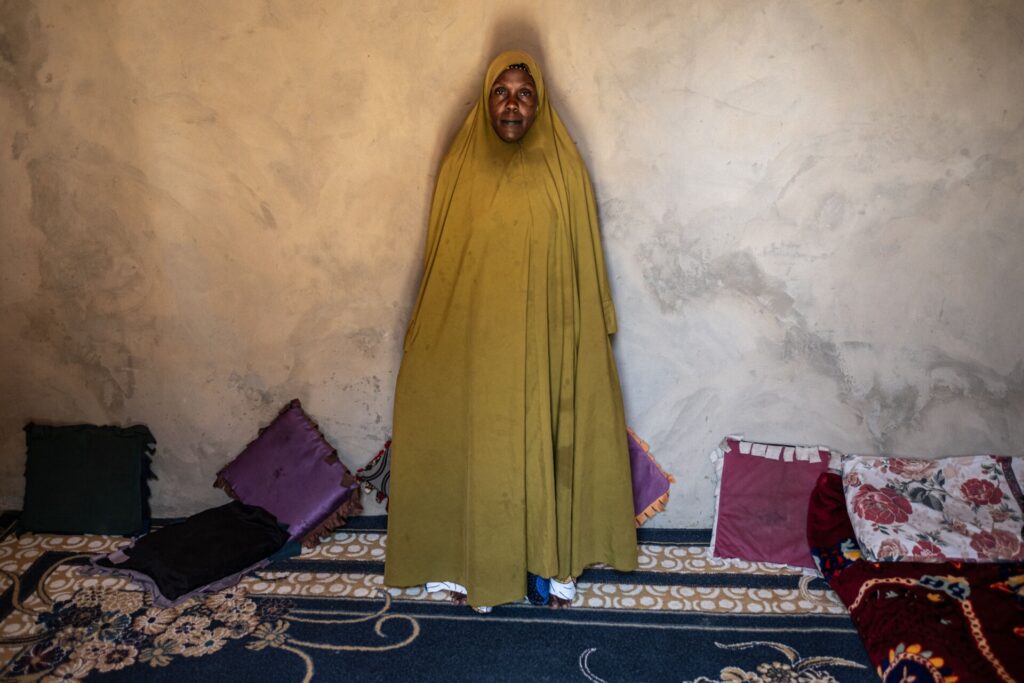

She fled into the bush with her three remaining children. For four months, they lived rough, trying to avoid wildlife and disease-carrying insects while scrounging for food and constantly on the hunt for clean water. Eventually, they made their way to the border with neighboring Chad and the opposite shore of the lake that her family had called home. They landed in a town called Bol, a new hub for those fleeing Boko Haram, a jihadist group founded in northern Nigeria in the 2000s. It is here, in her tidy if spartan room, that she pours us tea and recounts her ordeal.

Since 2009, the regions around Lake Chad, which straddles the borders of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and Niger, have become a major battleground for Boko Haram as the group spreads across the region. The lake, with its labyrinth of islands and canals that have emerged as the water level has dropped precipitously in the last half-century, has long served as a haven for insurgent groups. The region’s shifting landscape — further exacerbated by the climate crisis and the fluctuations of the lake — provides the perfect conditions for militants to establish bases, evade detection and coordinate attacks.

In the mid-2010s, the Boko Haram insurgency reached its peak after spreading across the shores of Lake Chad. The group’s operations became a regional issue, affecting not only Nigeria but also Chad, Cameroon and Niger — killing hundreds of thousands of civilians and displacing millions more, like Ya Gana and her family. As Boko Haram took hold and state-level attempts to quell the insurgency faltered, local leaders, groups and organizations saw an opportunity to help mitigate the crisis. New Lines traveled to Bol to see how communities in the Lake Chad region have taken on key roles, seeking to provide alternative methods of relief, reeducation and deterrence rather than relying solely on military responses.

To understand the reasons for Boko Haram’s presence in Lake Chad, one must go back to its origins in the early 2000s. “At that time, many young men migrated from Chad, Niger and Cameroon to northeast Nigeria,” says Oubadjim Dehba Desire, a Chadian analyst and researcher who has spent years studying jihadist insurgencies in the region.

The madrasas, or Quranic schools, of Nigeria’s northeastern Borno State have long hosted hundreds of students from across the region to study the sacred scriptures. In the early 2000s, an unschooled but articulate preacher named Mohammed Yusuf, who had spent time in Saudi Arabia and was deeply influenced by Salafist ideologues, began teaching an extreme version of Islam in the madrasas of Maiduguri. The radical doctrine found root among the scholars there, and soon the visiting students were taking their extreme views back home with them. “Northeast Nigeria is the birthplace of the ideas that would lead to the formation of Boko Haram,” Desire says. “This flow of young people from the region was inevitably influenced by its radical doctrine.”

When Yusuf was killed in 2009 by Nigerian security forces, his followers began a campaign of terror in the region on a staggering scale. Six million people in the Sahel have been impacted, according to the United Nations Population Fund. As the ideology spread across borders, including toward Lake Chad, so did the desire among young men to join Boko Haram’s ranks.

But beyond ideology, there are also structural factors that explain Boko Haram’s success in the region. The areas around Lake Chad are among the most marginalized in the four states into which the region is divided, and they are facing an environmental crisis on an epic scale, which indirectly feeds the extremist group’s aims.

Over 30 million people on the African continent depend on water from Lake Chad, which has shrunk to one-twentieth of its size in 1967 because of overexploitation and a changing climate. The altered landscape has become a haven for militants hiding among its thousands of floating islands, and their presence has also made one of the lake’s biggest sources of food and income — fishing — increasingly dangerous.

“For safety reasons, we cannot go further than 10, at most 15, kilometers from Bol,” Abdou Abdoulaye, a local fisher, tells us during our journey there. “Beyond that, Boko Haram controls the area. The only ones who go past that either have agreements with the group or risk being killed or kidnapped.”

Large Nigerian vessels often cross into Chadian waters and cast trawl nets that devastate local fish stocks and, with them, the diets of the local people. As people increasingly rely on agriculture and livestock to replace fish on their tables, long-standing tensions between farmers and herders over land use in the region are rising — a distrust that Boko Haram readily exploits.

Desire says that a combination of poverty, the state’s abandonment of the region and the lack of basic services like education and health care have created fertile ground for the group to recruit on the lake’s islands. “They exploited social frustration, promising a different life within the organization and, in many cases, financial gain.”

As a result, Chad has seen an explosion in recruitment to Boko Haram and mass displacement of people in the region around the lake. But with that rise in fighting has come the rise of civil society, working to counter the insurgency not with arms, but with forgiveness, rehabilitation and education.

Chad was drawn more deeply into the fight with Boko Haram in June 2015, when several suicide attacks targeted the capital, N’Djamena. The first two bombers detonated their explosives at the Department of Public Security and the central police station, while a car bomb in the courtyard triggered additional explosions. Moments later, as news of the attacks spread through the city, another vehicle detonated in front of the police academy. The final toll of the attacks was 38 dead, including the three suicide bombers, and 101 injured.

“The government’s response to the events in N’Djamena has been primarily military,” Abakar Adoum Mbami, a community leader in Bol, tells us as we sit in the shady courtyard of his home on the town’s outskirts. “But weapons alone can’t solve a phenomenon with such deep and complex roots.”

Mbami is part of a growing number of civil society actors working to address a broad array of problems brought on by the insurgency. While the army was struggling to quell the attacks, local associations and informal groups sprang up in Bol, initially working to find ways to house former fighters and women who were victims of Boko Haram. As the group’s influence blossomed in the region, Bol’s civil society then took on the task of providing clear information about Boko Haram to counter the myths and fake news that had drawn hundreds of young people to the organization.

According to Mbami, the authorities’ approach has gradually changed over the past five years. In addition to military and lake control operations, the government — pressured by the increasing number of repentant fighters leaving the organization — began to incorporate civil society’s independent response into its strategy against the Boko Haram threat. Mainly, the government has allowed local and international organizations to operate in the area. In some cases, it has partnered with or sponsored social projects.

One such public-private partnership is the rehabilitation center Mbami runs. The compound, encircled by a long gray wall, lies just beyond the center of Bol, where herders move their animals across the dusty road and out toward grazing lands. When we visit, Mbami shows us through the gate into a courtyard where a group of boys and young men are dozing in the sultry heat of the early dry season. They are young — between 13 and 19 years old — and thin, their faces bearing the marks of scarification common to the ethnic groups around Lake Chad. With our arrival, they stir and come sit with us on a mat in the shade.

“We were seeking money and an opportunity to study Islam,” explains one of the group’s older members, a young man from Baga Sola, the region’s other large city, which lies about 50 miles west of Bol. “But we quickly realized that inside the organization, things were different.”

Of the 10 or so former fighters at the center, some had been with Boko Haram for only a few months, while others spent several years in the group. Most had joined voluntarily, in search of the prosperity that is so hard to come by in the region. Others, including the center’s youngest resident, just 13, had been forced to fight after being kidnapped, much like Ya Gana’s four children, who remain missing. Regardless of how they entered the organization, all had found that life within Boko Haram was not what they’d anticipated. “We thought we would find freedom and job opportunities, but we were constantly monitored,” the young man continues. “We couldn’t talk to each other, or they would whip us.”

Their escapes were harrowing. “We were always being watched, so communicating was tough,” explains another of the young men. They fled under cover of darkness, on foot. They spent weeks in the bush, wandering at night, before finding an army post, where they turned themselves in to the authorities. With their amnesty secured, they were transferred to the custody of the regional government. Now they are in the care of Mbami and his colleagues.

One of the most crucial policy decisions in Chad has been national forgiveness for former Boko Haram fighters. As a result, hundreds have left the group and returned to their communities. But as the former militants have flowed back into the cities and towns around the lake, the infrastructure to receive and rehabilitate them has often been scant or inadequate.

Mbami’s rehabilitation center is a public-private venture. The reintegration program — a five-month stint during which the boys and young men receive vocational training in farming, fishing or livestock management — is funded by the regional authorities, but management of the facility and its day-to-day costs, including meals and the salaries of groundskeepers, are borne by Mbami, who is an influential landowner with agricultural and livestock holdings. He says some 200 young men and boys have passed through his gates since the facility opened in 2022.

It isn’t the only such facility in the region; others have opened, including in neighboring Baga Sola. And while the effort shows promise, says Hoinathy Remadji, an expert at the Institute for Security Studies Africa, “it lacks a more comprehensive approach.” Men and boys are often held together, programs aren’t age-specific, gaps in education for young fighters aren’t addressed and women who leave the group are left out of the reintegration process.

Days at Mbami’s facility pass slowly. When they’re not busy with training, the boys drink tea, pray or play cards. “Once out of the center, we’d like to find a job and maybe return to our families,” says the oldest of the group.

But while employment is a major hurdle to reintegration, Mbami says psychological reintegration can often be a bigger challenge. “They have internalized violent behavior,” he explains. The center has to help these young men rebuild their identities, away from violence and cruelty.

As a symbolic part of that process, Mbami invites his charges to participate in a special ceremony, in which they burn their old Boko Haram uniforms in a bonfire. “Our goal is for these young people to rid themselves of the ghosts of the past by burning what once tied them to the group.”

Many of the ex-combatants who end up in rehabilitation facilities like Mbami’s arrive there after voluntarily handing themselves over to the Chadian army. But before they do, the government’s message of amnesty has to reach them in isolated positions all around the islands and canals of the lake. That is where Kadaye FM comes into play.

Run out of a small gray and blue studio on the shore of the lake, the community radio station was founded 15 years ago by private donations and the help of international organizations. With its nearly 100-foot antenna, Kadaye FM reaches a potential audience of hundreds of thousands, with coverage extending as far as Cameroon. “During the years of the most critical emergency, we expanded the listening range as much as possible,” says Michael Ngomajita, the station’s program director. “We knew that for many in the lake region, radio was their only connection to the country and the news.”

In 2016 and 2017, during the height of the insurgency, Kadaye FM retooled its programming to make battling Boko Haram one of its primary objectives. Hoping to reach current fighters, would-be fighters and the community with clear, accurate and dissuasive information, the station added live talk shows and expert-led discussions addressing Boko Haram from various perspectives. “One program we’re particularly proud of was built around the live call-in segment with reformed fighters,” Ngomajita says. “The most striking thing is that the young people who told their stories were proud to speak out, to tell others about what they went through.”

Kadaye FM wasn’t the only station to tackle the insurgency. Across the Lake Chad region, community radio stations have played a vital role in addressing the Boko Haram crisis, partly due to the trust the public places in them. Apart from regular programming to deter fighters and disseminate information about amnesty and rehabilitation, stations coordinate during particularly acute moments of crisis. In 2017, when the region’s schools were closed due to fighting, several stations aligned their schedules to offer educational programs for more than 200,000 children in the region over the airwaves.

Just after the last notes of the evening call to prayer drift off into the night, a loudspeaker playing popular music starts up in the courtyard of Bol’s hospital, attracting dozens of children, teens and adults who come in from the street. As the crowd mingles, actor Amadou Garba warms up for his performance, painting toothpaste on his eyebrows, cheeks and chin to mimic the white beard of an old man. Tonight, he and his community theater troupe are staging a production about alcoholism and its effects. As the actors move across the makeshift, open-air stage, the audience laughs, jokes, gets angry and actively participates in the performance.

“We saw conflicts arising in our society and decided to engage ourselves,” Garba, 29, says of the group he co-founded more than a decade ago. They took to the streets to perform short, participatory plays out in the open to get the community involved in conversations about often difficult subjects.

“We do comedy, but at the same time, we try to make the audience think about current issues,” he says after the performance. Like so many of the small civil society organizations in Bol, Garba’s group has had to tackle the insurgency alongside their previous mission. Now, in addition to writing and performing theater pieces on intercommunity conflict, family issues and alcohol and drug abuse, Garba and his company stage pieces about the threat of Boko Haram, too.

The Women’s Association for Peace and Social Cohesion, another small association in Bol, has also had to pivot to include the impact of Boko Haram. “We handle various types of conflicts: community-based, family-related and economic,” says Daraya Yacoub Koundougou, the president of the organization. Her group moves through the rural areas around Bol and actively engages women in conflict resolution, tackling everything from inheritance to marriage to community problems. But since its creation in 2017, the organization has also provided shelter to numerous women who have fled from Boko Haram.

Ya Gana, who shared with us her story of fleeing Boko Haram, was one of them. “I hope to return to my village, but I don’t think that will ever happen,” she says. The fighting persists in her region and she does not know whether she even has a home to return to.

It is a fate that has befallen many. According to a report by the International Organization for Migration, of the more than 250,000 internally displaced persons and refugees in Chad, 55% are women. Uprooted from their villages, often by force, these women have few prospects for the future. Many lack education and are deeply traumatized by the violence to which they have been subjected. Meanwhile, the communities that take them in are already stretched thin, with jobs and resources scarce. “We can’t do much beyond offering shelter. At most, we can secure housekeeping jobs for them,” Daraya says.

While the Sahel is undergoing a period of significant transformation, the Lake Chad basin is also showing signs of this shift. The coups in Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali, the subsequent withdrawal of these countries from the G5 Sahel joint anti-jihadist force (of which Chad and Mauritania are still members) and the shift away from military partnerships with Paris and toward Moscow likely served as preconditions for the latest actions of the government in N’Djamena.

In November 2024, Chad threatened to withdraw from the Multinational Joint Task Force, a coalition formed in 2015 to combat Boko Haram, made up of all the countries surrounding Lake Chad. Later that month, Mahamat Deby Itno, the president of Chad and son of the late dictator Idriss Deby, unexpectedly ended the country’s military partnership with France. Chad took significant steps toward strengthening ties with Vladimir Putin’s Russia, marking a shift in its foreign policy. This allows Moscow to potentially solidify its influence in the Sahel, gaining leverage over countries that were previously aligned with Europe’s border management strategies. Amid these geopolitical shifts, the populations living in the Lake Chad basin are caught in the crossfire of regional and international power dynamics.

Despite the political instability and a conflict that has directly claimed the lives of over 40,000 people, activists and associations continue to heal the social wounds of the communities in Bol, as on other shores of the lake. “We got involved because the involvement of community leaders by the government’s strategy was not enough,” Daraya says. “But even if that is not enough, we will continue our work”.

The spontaneous efforts to promote peace and reduce extremist proselytising among the people of Lake Chad have been effective so far, despite the lack of long-term financial and institutional backing. According to Remadji, the security studies expert, without proper support there is a significant risk that the situation could worsen, as climate challenges further exacerbate the population’s already precarious living conditions. “What is needed is a vision for the future,” he says.

This article was published in the Spring 2025 issue of New Lines‘ print edition.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.