Bolivia’s Adolescent Pregnancy and Early Marriage Challenges Linger

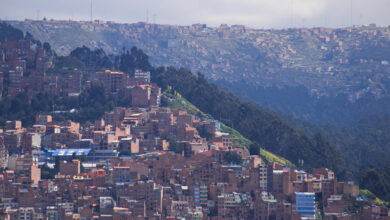

Bolivia continues to wrestle with adolescent pregnancies, particularly among girls under the age of 14, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive sex education, stricter legal frameworks, and ongoing support and resources for vulnerable minors nationwide within urban and rural communities.

A Critical Situation for Underage Girls

While official data suggest Bolivia has made strides in reducing teenage pregnancies, especially among those aged 15 to 19, the country continues to grapple with alarming cases involving younger girls—some as young as 12 and 13. In early April, a 12-year-old girl from a rural municipality in the Altiplano region gave birth in an ambulance in route to a health center. This recent incident, reported by the national Ombudsman’s office (Defensoría del Pueblo), underscored “a critical condition for someone her age.”

Tragically, this girl’s pregnancy resulted from rape by her teacher, who now remains in preventive detention. Her case shows a common problem in Bolivia. Structural issues there permit sexual violence, plus teen pregnancies, to continue. Authorities state that incidents like this often stay secret. When they become known, official reactions can be late or poor. This exposes victims to more damage.

According to official figures presented in the 2023 National Demographic and Health Survey (EDSA), the specific fertility rate among adolescents aged 15 to 19 dropped from 84 births per 1,000 in 1998 to 48 births per 1,000 in 2023. These numbers are more encouraging in urban areas (35 per 1,000) than in rural ones (88 per 1,000), pointing to disparities that demand greater attention. However, for girls younger than 14, the situation remains dire, and cases involving sexual abuse are particularly concerning.

In conversation with EFE, Ximena Pabón, Programs Coordinator for the Fundación Alianza por la Solidaridad, noted that between 2018 and 2023, pregnancies among girls aged 15 to 19 dropped from 18% to 14%. While she sees progress in that demographic, she stressed that “this decline does not apply to girls under 14,” based on data from the Ministry of Health. These underage pregnancies often arise from sexual violence, in some instances “resolved” through forcing marriage between the victim and the perpetrator—an arrangement that further entrenches harmful societal norms.

Societal Barriers and Limited Sex Education

A great difficulty when solving adolescent pregnancy in Bolivia is an unwillingness – both in institutions plus in culture – to give thorough sexual education. According to Pabón, parental pressure frequently forces schools to avoid topics related to sexuality out of a mistaken belief that such information will encourage teenagers to have sex earlier. The data does not back this belief, she told EFE. Open plus accurate education usually postpones sexual activity and helps young people in decision-making about their reproductive health.

Several schools do not have well-developed sex education plans in place. Educators often confront resistance from guardians or local authorities. The parties take issue with accepted standards of behavior or traditions. Because of this, teens depend on doubtful places for data. Examples are television, online sites, and friends. Such places can overstate or twist romantic or physical partnerships. Pabón stated that this problem requires attention. Popular entertainment and computer games, along with some song lyrics, often send communications that overly focus on the sexuality of young girls or make harassment seem unimportant.

In addition, systemic problems remain. In Bolivia, the Family and Family Procedure Code lets people marry at 16 if their parents agree. Although there is a bill in the Senate pushing to prohibit marriage and free unions among or with minors under 18, it still hasn’t been enacted. Citing the influence of international recommendations, proponents of the bill argue that closing loopholes would protect vulnerable minors. Critics, however, point to cultural traditions and fear that eliminating any form of parental input might ignore local contexts.

In practice, these gaps lead to scenarios where families, communities, or authorities collude—intentionally or not—in early marriages designed to “legitimize” a pregnancy or “address” a rape. This method creates a situation where those who have survived abuse must continue interactions with their abusers. It also causes them to lose chances for schooling plus social development. These changes would help them escape abusive patterns.

Healthcare access is another critical concern. Since 2014, Bolivia has upheld a Constitutional Court ruling that a simple copy of a sexual abuse complaint or a medical report indicating the mother’s life is at risk allows access to a legal termination of pregnancy. Yet, many health professionals remain reluctant to carry out the procedure, citing moral or religious reservations. Pabón lamented that this “has severely limited women’s and girls’ rights” and contributed to unsafe abortions or forced motherhood among children.

Proposed Legal Reforms and Future Steps

Observers acknowledge Bolivia shows a decline in teenage pregnancies among 15 to 19-year-olds. This reduction suggests some favorable developments. For example, access to contraceptives improved. Sexual health campaigns showed small gains. Public discussions experienced slow changes, too. In an interview with EFE, Pablo Salazar, the Bolivian representative of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), highlighted how the downward trend “is not uniform across all social groups,” reiterating that rural communities are often left behind and that younger adolescents remain especially vulnerable.

Salazar further pointed out that for girls between 10 and 14 years old, the conversation goes far beyond access to contraceptives. It is about “education, protection, and changing harmful cultural norms.” He emphasized that Bolivian society must undertake broader shifts in how it views gender, power dynamics, and the responsibilities of adults who come into contact with minors.

The Senate is considering a bill to prohibit any marriage or informal union with children below 18. This action is a real move to safeguard girls. Supporters state the law, after its passage, will deal with loopholes used to excuse unions with girls underage. Approval of the law plus its later application presents difficulties.

Organizations like Fundación Alianza por la Solidaridad and UNFPA continue to push for improved education about sex. Without straightforward talk in schools besides at home, young people deal with sexuality using rumors and incorrect information. This makes early and unplanned pregnancies more likely. Adequate teacher training, culturally sensitive curricula, and parental engagement are widely cited as keys to progress.

Pabón, who has long advocated for an intersectional approach—one that recognizes the diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds in Bolivia—underscored the urgency: Specialists emphasize that broad change needs combined work across many areas. By making the legal system better so it guards young people from sexual abuse and underage marriage along with the goal of healthcare providers observing decisions about reproductive freedoms, a plan with several steps is important to decrease pregnancy among teenagers. “If we tackle these issues with real political will—through legislation, education, and enforcement—Bolivia will be closer to ensuring a brighter, healthier future for all its girls,” Salazar concluded.

Also Read: Peru’s Enduring Drama: Eight Presidents, Endless Judicial Battles

Bolivia’s experience underscores the fragility of progress when it comes to adolescent reproductive rights. Even as the country reports some positive trends among older teenagers, younger girls remain disproportionately at risk. Bolivia currently has a decision to make: address societal biases plus failures in the system or permit a lack of discussion and inadequate laws to continue violence besides coerced parenting. People working directly with victims want new law suggestions, together with a greater understanding of complete sex teaching, to at last offer Bolivia’s most at-risk young people a better opportunity for secure, healthy futures.