The Overlooked Reality of Shareholder Activism in China: Defying Western Expectations

China is known in the West for many things. However, a rules-based market for shareholder activism is not one of them. President Xi Jinping is (in)famous in the West for demanding “that businesses conform to the aims of the Communist Party”.[1] The newly appointed boss of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) – China’s equivalent to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – has earned the sobriquet “Broker Butcher” for his alleged zealous crackdown on traders in the 2000s. Western media regularly reports on “[b]illionaire tycoons, including Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, [being] driven underground or imprisoned after criticizing the government”.[2] This is not exactly an environment in which one would expect to find a vibrant rules-based market for shareholder activism – especially with state owned enterprises as the target of such activism.

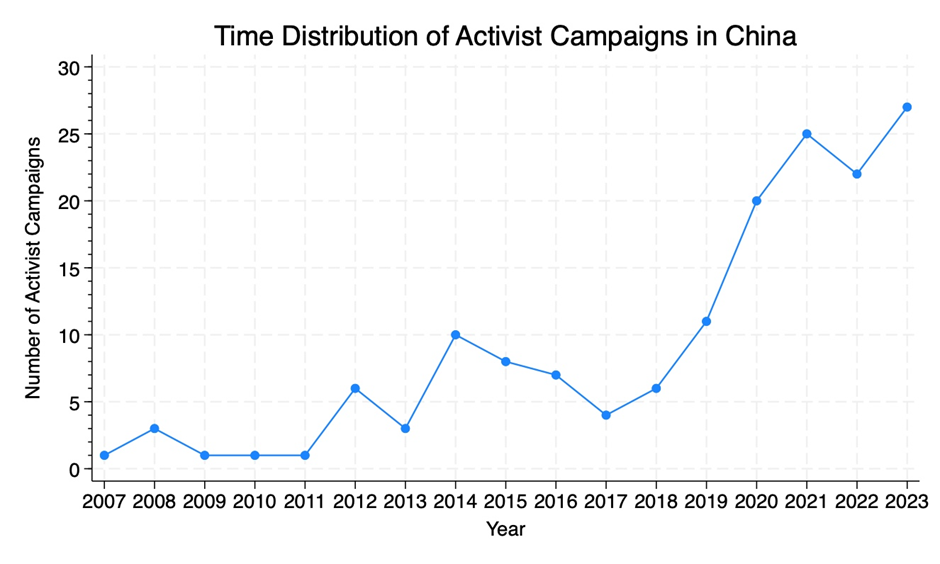

And yet, the in-depth empirical and case study evidence in our new ECGI Working Paper – The Overlooked Reality of Shareholder Activism in China: Defying Western Expectations – reveals that shareholder activism in China is thriving. Based on our unique hand collected data, there were nine times as many publicly reported shareholder activist campaigns against listed companies in China in 2023 (27) as in 2008 (3) – with over two-thirds of all the shareholder activist campaigns since 2007 occurring in the last five years (see Table, below).

More unexpectedly, our empirical analysis reveals that whether the target company is a private owned enterprise (POE) or state owned enterprise (SOE) has no statistically significant effect on the success of the activist campaign, no matter whether the activist is a state owned or privately owned investor. In fact, contrary to Western conventional wisdom, private shareholders undertake, and more often than not succeed, in activist campaigns against so called “national champions” – the name bestowed on the largest, most politically powerful, SOEs in China.

Surprisingly, 78% of activist campaigns against national champions were brought by private activist shareholders – 57% of which succeeded. One such activist campaign involved retail investors organizing on a social media platform called “snowball” [雪球] to publicly object to the dividend policy of a powerful national champion. Led by an anonymous online investor who went by the colorful handle “Legend of the Red Scarf” (perhaps China’s answer to “Roaring Kitty”) the campaign forced the hand of the target’s management to adopt a generous dividend payment policy after it had refused to pay dividends for over a decade – conjuring up images of WallStreetBets meets China.

The other side of the rules-based market coin is evident in our empirical findings that there is no statistically significant difference in the success rate for state-controlled activist shareholders (SAS) and private activist shareholders (PAS), regardless of the political status of their targets. Again, contrary to Western conventional wisdom, over 50% of activist campaigns launched by an ostensibly powerful state-controlled activist investor – that is, a national, rather than local, SAS – failed when the target was a POE. Our in-depth review of shareholder activist cases even revealed a POE using aggressive and illegal tactics to defeat the campaign of a state-controlled activist shareholder (SAS) and the state following due process to challenge the sharp practices of the POE in court. This reinforces the picture revealed by our empirical findings that China has developed a rules-based market for shareholder activism.

Another interesting feature of shareholder activism in China that our empirical and case study analyses illuminate are cases involving activist campaigns where state-controlled entities are both the activist shareholder and target company. The details of these cases suggest that shareholder activism in China may also serve as an important corporate governance mechanism among government entities to promote good corporate governance, improve efficiency, and weed out corruption. We also uncovered cases in which SASs from different provinces compete as activists to influence target companies akin to what one would expect to find between private parties – providing further evidence of a rules-based market for shareholder activism in China that promotes government and corporate governance efficiencies.

Taken together, our empirical evidence, including our regression analyses in which we coded shareholder activists and target companies based on their level of political power, suggests that shareholder activism in China is driven by rules-based market forces – the opposite of what one would expect based on conventional wisdom about the rising influence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Chinese corporate governance in the President Xi era. This meteoric rise of shareholder activism in China since 2019 dovetails with regulatory changes in Chinese corporate governance that increased the incentives for shareholder activism – further suggesting the importance of rules-based market forces.

This conclusion is bolstered by empirical evidence that other aspects of shareholder activism in China conform to what one would expect in a rules-based market for shareholder activism driven largely by financial incentives. Shareholder activists that hold a larger percentage of the target company’s shares have a statistically significant higher chance of succeeding in an activist campaign. Moreover, an analysis of the success rate of shareholder activism campaigns reveals that targets of successful activist campaigns had a return on investment (ROA) over 50% lower on average than those in unsuccessful campaigns. Again, ironically, this wave of shareholder activism has occurred at the precise time when both popular media and leading academics suggest that China, under the tightening grip of President Xi, has been decidedly moving in the opposite direction – ostensibly enhancing the CCP’s involvement in corporate governance and thwarting the rule of law.

The fact that much of what goes on in shareholder activism is unobservable is a universal characteristic that exists in markets globally and confounds empirical research on this topic. It is possible that there are unobservable cases in China in which politics prevents shareholder activism from arising in the first place – but if this were the case it would still not explain away our observable empirical evidence of the recent wave of shareholder activism in China. It is also possible that a high-level empirical analysis may fail to detect idiosyncratic individual cases in which politics played a definitive role in a shareholder activist campaign.

To interrogate this possibility, we undertook an in-depth case study analysis to find any evidence of political influence playing a significant role in individual cases of shareholder activism. It is noteworthy that we did not find a single case in which a local state-controlled shareholder activist attempted to even launch a campaign against a national champion – suggesting that the political hierarchy between local state entities that are shareholders and national champions may serve to quell such campaigns. It is also noteworthy that the nature of the campaigns in which SOEs – particularly national champions – are the targets may be permitted (or even promoted) by the government where they dovetail with a government policy to strengthen minority shareholder rights in China. Also, we uncovered a single case involving a national champion in which politics may provide an explanation for an unanticipated outcome. Overall, however, our case study analyses further confirm our empirical findings that the recent wave of shareholder activism in China appears to be primarily driven by rules-based market forces.

Finally, it is worth noting that at the end of 2023, China’s Company Law underwent a significant amendment, with the new Company Law taking effect on July 1, 2024. The 2024 Company Law, the second significant amendment since the enactment of China’s first Company Law in 1993, has as one of its key focuses the empowerment of minority shareholders. Among the changes, the threshold for shareholder proposals in listed companies has been lowered to 1% from 3%, and shareholders are explicitly granted broad inspection rights, with the scope of inspection extending even to wholly-owned subsidiaries. Additionally, shareholders are now allowed to initiate double derivative suits. This portends that the recent wave of shareholder activism in China is only likely to grow.

Fans of rules-based markets should be heartened by our findings. Chinese companies have become world leaders in many important industries. Over the past 15 years, China has had the world’s largest market for initial public offerings and the world’s second largest stock market, which has grown five-fold in the past decade. To think that this success is the result of a system in which the government uses its political influence to dictate corporate governance outcomes gives far too much credit to the Chinese government – and far too little credit to rules-based markets. There is a reason why the USSR regularly had shortages of toilet paper and why it did not have shareholder activism. China now has an abundance of both.

EIN Presswire does not exercise editorial control over third-party content provided, uploaded, published, or distributed by users of EIN Presswire. We are a distributor, not a publisher, of 3rd party content. Such content may contain the views, opinions, statements, offers, and other material of the respective users, suppliers, participants, or authors.